“Don’t you worry, no waste is wasted in this country” – Najib Othman, plastic factory owner.

This is what the owner of a plastic manufacturing company had to say as we toured his recycling factory in Aleppo City. When we probed further about other factories that recycled materials other than plastic, he confirmed that in Syria there is an entire market dedicated to recyclable materials.

How accurate was this statement? Could it be true? Nothing wasted in Syria!? Let us start from day 1 of our 100-day mission to understand the recycling scene in Syria in general with a focus on the current attitudes and behaviors towards recycling at the household level.

The main reason for our interest in this topic emerged from the fact that traditional recycling practices were prominent and widespread within Syrian households. For example, leftover frying oil turned into scented homemade soap; every 3-5 empty plastic yogurt containers being exchanged at the grocery store for a full container of yogurt; old bread and eggshells being collected as chicken feed.

In fact, many of these practices were so profitable that peddlers used to make street announcements and knock-on doors to buy old or broken household items or exchange them with new ones. For example, an old broken plastic chair can still be exchanged, in many cases on a 1-4-1 basis, for a brand-new chair with little money. Although some of these practices still exist today, they are limited in scope and reach due to the crisis.

The second reason for our interest in this topic is the fact that recycling took a downward trend and became somewhat of a neglected topic in Syria. Given the country has been through a 10-year crisis, aggravated by the deterioration of socioeconomic conditions, recycling no longer became a priority for many Syrians. Sadly, most topics related to climate action or the environment receive very little attention. Notable, there have been a few local and international initiatives over the years that tackled the recycling topic, however, they either were limited to awareness campaigns, or introduced recycling installations without proper instructions, which prompted people to use them the same way they use current waste bins which defeated the purpose.

From this scene, our challenge was born and being the Accelerator Lab that we are, we had some piercing questions: What causes home recycling to diminish during exceptional circumstances? Building on the quote above, how did this problem lead to the growth of an informal sector? How can we encourage people to go back to the positive recycling practices that were engrained in Syrian society? What kind of barriers face people who have the intention to recycle but do not know how?

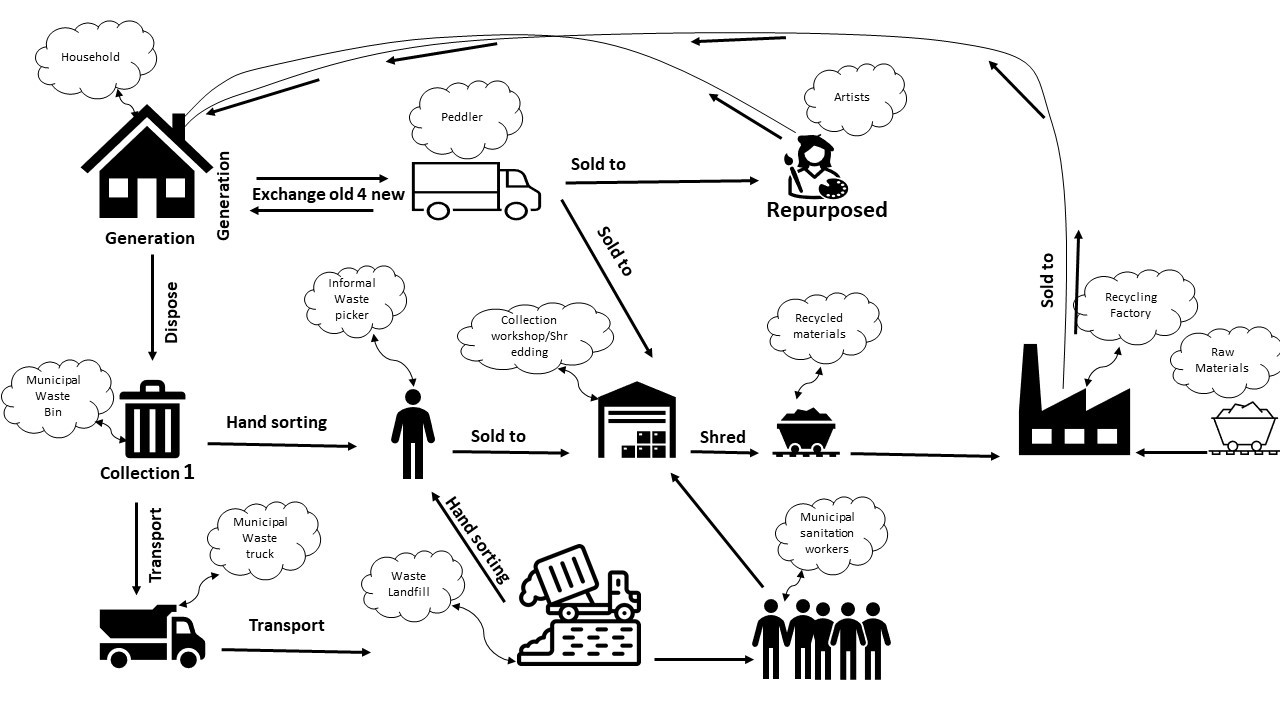

To answer these questions, we needed to look at recycling not only from a household perspective but also from a system perspective. Recycling, after all, is a small part of a broader system that starts with the generation of waste and either ends up in a recycling factory or a waste landfill. Within this system there are existing value chains for most recyclable waste produced. Moreover, many of these value chains are far reaching and specialized. The problem, however, is they are considered informal, operate in unhealthy conditions and are disorganized.

Recycle or Reuse? That is the question.

“We don’t have the luxury to throw anything away or to recycle” – S.T, Mother

We were curious to know more about the ways of which people are reusing recyclable materials. So, we interviewed mothers in focus group discussions, it emerged that mothers are the ones who are responsible for household waste management. We also interviewed sanitation workers who gave us everything we needed to know about what type of waste is most generated and what happens to it after it is removed from street waste bins.

To our absolute shock, we discovered that although some traditional household recycling practices were diminished, others were born out of an economic need in low-income households. One of the women we interviewed informed us that recycling is a rich person’s luxury and not for poor people. “Poor people cannot afford to throw anything they can still reuse”.

Some examples that arose from the discussions included reusing plastic containers for food storage, cleaning material refills, and freshwater storage. An unhealthy finding was that these women burned non reusable plastic for heating. As for cooking oil, women said they reuse it until it evaporates. They were perfectly aware of the health consequences owing to the carcinogens produced, but they said they have no other option; they cannot afford the increased price of food staples. Even women who came from areas with better living conditions stated they do not recycle; they reuse.

We also discussed what type of motivations might encourage society to recycle. Women from middle income households expressed bluntly that the only thing that will motivate them to recycle is to have something in return “Give us something to give you something” one woman said. They viewed recycling as “not worth the effort”, it is extra work that is useless. Another woman said, “we sometimes segregate plastic bottles from other types of waste, but there is only one waste bin for everything in our neighborhood, so trash will end up in one place anyway”.

When we pointed out that there are few recycling bins in the city, women immediately replied they don’t use them because they don’t know how to, and even if they used them the municipal waste workers will empty recycling bins in one place, so again “why bother”.

Valuable Waste: “One man's trash is another man's treasure”

What happens to waste after it is dumped in the waste bins? Both direct observation and FGD with waste workers showed that there is a significant increase in the number of informal waste pickers. Waste picking is the new source of income in town! Despite the many health risks posed by handling waste, especially during the time of COVID, you can see women, men, children, and elderly digging the treasures out from a neighborhood waste bin. Plastic bottles, old plastic hoses, metal cans, batteries, dry carton boxes, and many other “valuable” and exchangeable materials will be dug out of the bin and placed expertly in separate bags.

The segregated waste will be then sold to a waste collection point known as the “waste shredding workshop”. There is an agreed market price for each type and amount of recyclable waste collected. This price goes up and down based on the need of the market. The need is defined and controlled by the factories’ owners or waste exporters, who buy recyclable materials from the waste collection and shredding workshops.

In Aleppo we visited different locations that either collected, reused, recycled, or sold recyclable materials. We visited repurposing factories, used cardboard stores, plastic collection stations, and paper arts & crafts workshops. These visits made us realize that most recyclable materials of perceived value are either recycled or reused. Taking us back to the quote at the beginning of this blog post “Don’t you worry, no waste is wasted in this country.”

The reason why there is an increased need for recyclable materials is, as explained by the recycling plastic factory owner, “because buying virgin materials is becoming more expensive in each passing year”. Before the crisis and the recent economic sanction, recycling was not worth the effort. For manufacturers, using raw virgin material is cheaper, needs less work and is more profitable. The current economic sanctions and COVID-19 restrictions make import opportunities limited and more expensive. The decision to resort to recyclable materials was made by manufacturers as an alternative solution that can save their work. Environmentally speaking this is good news! When recycling works, less virgin and natural resources are used, less trees harvested, less water and energy used, and consequentially less materials littered. However, there must be a way to do it better and with less health risks.

To summarize the learning from our exploratory phase: Households generally do not recycle -- they reuse recyclable materials. There is no proper formal infrastructure for recycling in the cities. “Valuable waste” comes from the rich side of the city not the poor side. Waste picking has increased significantly during the past few years. There is a market for almost every recyclable waste.

Where do items of no value go? Where do we go from here?

The real problem at the household level is products with little to no value that are difficult to collect. Consequently, they cause the biggest environmental pollution and provide an opportunity to address the underlying attitudes and behaviors towards recycling such as light plastic bottles, plastic bags, cooking oil and food packaging.

Moving forward, our exploration will focus on surveying people’s current attitudes and behaviors on home recycling and the kind of incentives they are interested in. Next, we will use behavioral insights as a philosophy to design a portfolio of experiments under the banner of Gamification and Economification of household recycling. Stay tuned for our next blog!

Locations

Locations