The organizational design of the UNDP Accelerator Labs have, un/fortunately, made our teams a good partner in crisis across the globe. For those of you who may not know, the Accelerator labs are not an innovation unit and we do not simulate a traditional accelerator or incubator, the labs launched in 91 countries so we can prioritize learning at speed, in development. While development does so much, we are not learning fast enough from each other and the people we serve to be able to reach SDGs by 2030.

I highlight the set-up distinctly because I believe it is a key factor in how we would look and talk about “data in development, and action in crises”. While our colleagues across UNDP do a lot of heavy lifting and substantial hard-work, the Labs were modeled as an agile organizational team that does not sit in any one portfolio, this allows us to gather collective intelligence from seemingly disparate pockets inside the organization, and user-led intelligence from outside the organization. Our work lies in connecting the relevant dots so we can assemble learning experiments at speed in transformational development areas.

Accelerator Lab Learning Cycle

This proved to be quite important in light of a crisis as large and wide as the Beirut Blast of August 2020, dubbed as the largest peacetime explosion in history. All of Lebanon was shaken and remains, no staff member national or expat was spared the impact.

Crisis means chaos, In complex system science this domain is not governed by order, best practice, or strategy — one can only act with what one has, and where one is.

“A leader must first act to establish order, then sense where stability is present and from where it is absent, and then respond by working to transform the situation from chaos to complexity, where the identification of emerging patterns can both help prevent future crises and discern new opportunities.”

— David J. Snowden and Mary E. Boone

3 days after blast, the leadership of our country office along with the agility of the Accelerator Lab allowed us as a country office to leverage the mobility and expertise of UNDP’s Surge Data Hub, where we all came together to produce a data pipeline that continues to this day, 7 months post blast.

When it comes to Data, especially in development, I would like to walk you through this journey by breaking it down to 3 areas.

- Assessment & collection

- Analysis & Access

- Culture & workflow

Assessment and Collection

Our colleagues at the Surge Data Hub, and as part of the Country Support Management Team, had been already rolling out Socio Economic Impact Assessments (SEIA) across the world, in more than 45 countries, in post COVID crises context. The SEIA is a form of modular library that allows co-design in crises context and quickly. Beirut was no different and ALL different at the same time.

In an attempt to practice both a trauma informed approach to data-collection and to capture a critical time window post blast we rolled out SEIA across Beirut and adjacent suburbs using Facebook Ads. This approach was particularly useful since sending out enumerators to people’s homes was literally impossible. The method has its benefits and its shortcomings*, but we were able to collect 9,000 submissions in under 6 days during the second week of blast, which would traditionally take at least 3 weeks.

The nature of Facebook Ads presents an evident assessment exclusion factor around internet access, technology, and social norms of some family units. It does however allow for choice, reduces cognitive load and assessment fatigue. It is also important to mention that we complemented this approach with phone surveys, and SMS as well.

Defining Data with an assessment & collection lens, is what the development world is very well versed in. Almost an exclusive definition for data in development has become sourcing, collecting data, and of-course monitoring and evaluation. While having data is important, and having such a snapshot of impact at such a critical time is key, the SEIA value was in the way that such a data-product triggers a snow-ball effect in the conversations, decisions, and teams it comes across.

Analysis and Access

As a Lab, taking cues from grass root innovators is one of the main drivers behind our work. We saw communities rise up within days in Beirut with the sole aim of using data to better coordinate aid and avoid duplication. Work done by GlobalShapers Beirut, Openmaplebanon.org, Beirut Relief coalitions inspired a lot of what we tried to do.

When it comes to analysis and access we need to shift our mindsets from reporting and data-sets to more basic questions:

What do you have? What have you made available? and how?

Trying to answer these questions transforms “data” from the space of speciality and exclusive technical speak into the space of “data-informed and empowered” discussions, designs and actions i.e “Engagement”.

What does it mean to “design access”?

We tested out several ways to share data, till it became clear that “sharing data” is not the same as “designing access”. Our recovery work as a country office is centered on a Leave No One Behind framework, and it clearly outlines “Data-driven” and “human-centered” as 2 of 7 main inclusive recovery pillars.

“The more ubiquitous data becomes, the more we need to experiment with how to make it unique, contextual, intimate. The way we visualize it is crucial because it is the key to translating numbers into concepts we can relate to.”

— Giorgia Lupi, Data Humanism, The Revolution will be Visualized

Big data is overwhelming; to the humans consuming it, and to the humans it tries to represent. Accordingly, we must experiment and assess the many ways we can share and rally around data. While always being aware of the cost we accrue from: accumulating data, the emotional and cognitive toll in collection and analysis, the possible mis-use mitigation, and data privacy and sensitivity.

Recovery in Beirut’s context holds innumerable layers of complexity, and we need a data approach within ourselves and all 3RF partners that can:

- Embrace complexity

- Elevate people’s intersectional representation

- Understand data limitations

One of the ways we are experimenting around this topic is by designing access to our SEIA data through an interactive data story which will be published by end of April 2021. We want to ensure that the data speaks in a visual narrative, while also allowing interactive engagement features that help navigate the complexity of Beirut neighborhood’s vulnerabilities from different outlooks.

Below I share a sneak peek into the type of data we would be sharing, If you are interested in the full data story you can share your email address here and you will be notified as soon as our SEIA data-story gets published on our UNDP website.

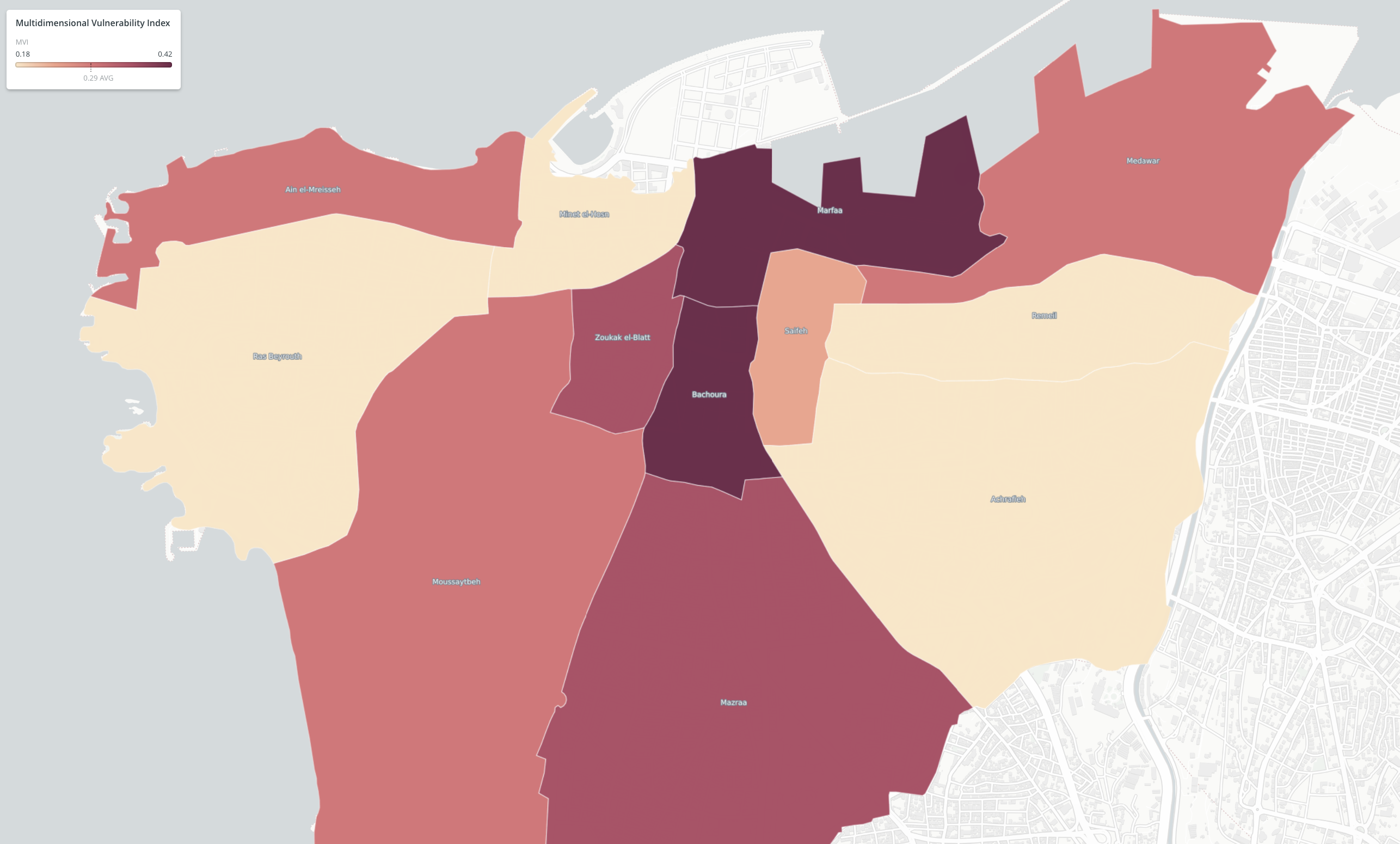

To answer the question of where the most vulnerable groups exist within the city, we use the multidimensional vulnerability index to assess intersectional vulnerabilities at the household level, and then aggregate to the neighborhood level.

We also include a generative exploration on “What defines a neighborhood”, we consider an alternative method of defining what a neighborhood is. In particular, we consider the effect of different neighborhood sizes with respect to Beirut’s population.

Our study considers two dimensions of resident access to facilities (particularly hospitals and schools): first, their physical distribution, and second, a measure of these facilities to attract residents to specific locations across Beirut. Above visual expresses different attributes of accessibility, Top and bottom figure respectively: Hospital access in Beirut, and school access in Beirut. More details on upcoming story-page.

To produce this analysis we worked with two data scientists on their doctoral journey at UCL Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis ( Mathew Kok Ming NG , Melda Salhab)

Culture & workflow

Leaving No One Behind meant that our recovery work took shape in an integrated approach to support neighborhoods. We started with one that has historically suffered variant vulnerabilities which were fiercely stretched after the Beirut explosion. The Karantina Neighborhood.

This is the more granular data work that is often dismissed as “details” or “tactics” but in fact can be quite instrumental in ensuring human centered recovery plans.

This is Rita, she lost her house, her husband suffered variable injuries, lost his livelihood as his taxi was destroyed, and her daughter lost her hair styling equipment that allowed them to source income.

For us to serve Rita and the many many people like her, we have to treat data internally, not just as a piece of information but as a workflow language.

Image source Tower of Babel, never went up as far as it could simply because people lost a common language in practice.

Image source Tower of Babel, never went up as far as it could simply because people lost a common language in practice.

As large organizations, we need to look at data as more than just a tool. We need to look at every occasion for input, analysis, and communication as an opportunity to gather, discuss, and action. Rather than data at the sole discretion of an information manager or engineers, it should be the vascular blood flow that circulates around each and every contributor of the recovery journey.

With an off the shelf product called Activity Info, capacity in information management, and a designed and supported collaboration environment, we piloted a cross cutting data and engagement team which allows an easy way to open up our data to each other and easily select portions of it to share with partners.

Dashboard prototype of integrated recovery efforts in Karantina using power Bi

As we still test this out, it is important to say that this is not necessarily new and as Labs, “new” is not our objective, however we try to take the tools of the few and open them up to many, so we can improve data agency, autonomy, and the opportunity for creative combination and design.

Locations

Locations