This blog, authored in partnership with Shazana Agha, Women’s Aid Organisation (WAO), is part of UNDP Malaysia's Kisah series, which explores COVID-19 impacts through the dual lens of conversation partners at the front lines, and through UNDP’s programmes and priorities. ('Kisah' is a Malay word that means ‘story’ and ‘to care, to take interest’.) To participate in Kisah, or to find out more, email the UNDP Accelerator Lab Malaysia at acclab.my@undp.org.

*Pseudonyms have been used in this article to maintain the privacy and confidentiality of survivors.

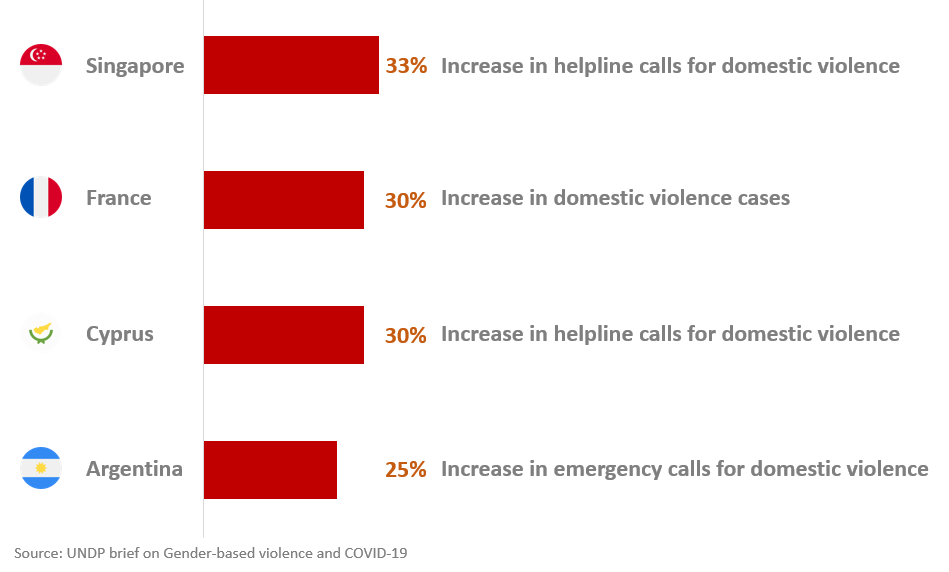

With governments across the world enacting lockdown measures to curb the spread of the COVID-19 virus, there have been many unintended consequences. Among them is the alarming increase in reports of domestic violence (DV) and intimate partner violence (IPV) observed in countries worldwide.

Increase in gender-based violence during COVID-19

The uniformity of increased gender-based violence (GBV) across the world is worrisome. UNDP, together with other UN agencies, is working with over 40 governments to address this issue. In this article, we explore the scenario in Malaysia.

+++

Lina* was experiencing severe abuse by her husband when she decided to reach out to WAO, an organisation that provides support services for survivors of gender-based violence. She had suffered multiple blows to her back, been choked, and was prohibited from leaving the house. WAO contacted the police who took immediate action and rescued Lina from her home on the very same day.

In a different state, Chandra*, another domestic violence survivor, reached out to the local police for help in two separate instances, but was told that they could only respond to her reports of domestic violence after the Movement Control Order (MCO) was lifted.

Before the MCO came into force in Malaysia, Claire* decided to leave her home with her children, knowing all too well the violence she would have to endure while living in quarantine with her abuser. She lived in hotels and her car for a few days, before finally finding refuge at a shelter run by a local non-governmental organisation (NGO).

Nadia* escaped her abusive home and began living in her car. Unlike Claire, Nadia was not able to find adequate shelter and was eventually questioned by local authorities who were carrying out their duties in enforcing the MCO. She rented a place to stay for one night and then returned to her abusive situation.

+++

The stories of Lina, Chandra, Claire and Nadia may not be representative of the experiences of all domestic violence survivors during the MCO in Malaysia. Nonetheless they provide a glimpse into some of the key challenges endured by survivors in accessing justice and support—challenges that often existed before the pandemic began. The UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women (UNTF EVAW) surveyed 122 of its grantees from 69 countries worldwide and found that key factors exacerbating violence included food shortages, lockdowns, unemployment, and economic insecurity.

Shelters offer critical support for survivors, but are lacking

Shelters are a crucial form of support for survivors as they prevent them from having to make the choice between remaining in an oppressive and abusive relationship or facing the prospect of homelessness and financial uncertainty. Yet, access to this essential service was already inadequate in Malaysia before the pandemic. Minimum standards for support services, developed by the Council of Europe and endorsed by many international organisations such as UN Women, recommend a minimum of one ‘family place’ in a women’s shelter per 10,000 people, but Malaysia only has about one family place per 70,000 people. One ‘family place’ is defined as space for one adult and the average number of children in a family.

When the MCO was declared on 18 March, the dismal state of shelter provision was further compounded by the exclusion of shelters from the government-identified list of essential services allowed to operate. During this time, WAO received calls from survivors trying to escape abuse in their home. Yet, the best support WAO could offer during the initial phase of the MCO was to place them on a waiting list and suggest that they seek help within their own support systems, i.e., family and friends. With the support of the Selangor state government, WAO was later able to organise temporary emergency shelters for survivors including making hotel rooms available for shelter . A more proactive government response in increasing the number of temporary shelter spaces for women would significantly improve their safety, especially during crisis like this. France has taken an innovative approach to this—it has made 20,000 hotel room nights available to women needing shelter from abusive situations during the COVID-19 outbreak.

First responders are often overwhelmed

Another crucial form of support for survivors are first responders such as police officers, social welfare officers, and crisis hotline operators, who serve as important connecting points for survivors to access legal protection and other forms of support. As illustrated through the cases above, first responders can be a major determining factor in whether survivors remain in or escape abusive situations. Yet, insufficient funds are being channeled to these incredibly important human resources.

For instance, in December last year, it was reported that Malaysia had a ratio of one social worker for every 8,756 Malaysians, far behind the ratio of several developed countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Singapore and Australia.

As a result of low human resources, social welfare officers are often stretched into handling multiple issues ranging from domestic violence to ‘destitute persons’, flood relief work, and staffing other support services. This is particularly worrying as it overwhelms officers and affects the quality of services received by survivors. During the MCO, we see this being further compounded by a marked shift in priorities of frontline officers, who are tasked with more pressing and immediate public health concerns such as enforcing social distancing measures or distributing food and financial aid to economically-affected communities.

In early April 2020, Talian Kasih (the national crisis hotline set up to respond to members of the public facing social issues) reported a 57 percent increase in calls since the beginning of the MCO, most of which were said to be related to aid enquiries. The government made several public service announcements (PSAs) to spread awareness about the hotline; as a result, the number of domestic violence related calls began to increase, showing that increased awareness encouraged women to step forward and report their situations.

Throughout the MCO, WAO and other organisations received mixed reviews from survivors in connecting with Talian Kasih. Some reported receiving prompt responses while others reported experiencing difficulties. For example, one survivor said she made seven to eight attempts to contact the hotline but was unable to get through. Another survivor was instantly connected to a social welfare officer by a Talian Kasih operator and obtained an interim protection order within a few days after a police investigation was opened. The heart of the matter is this: the lack of a comprehensive and coordinated response to gender-based violence in Malaysia means that not all survivors receive the protection they need and easily fall through the cracks in the system. Within the context of a pandemic crisis, this reality is further amplified.

In extreme situations such as lockdowns, first responders such as police must be given special operating procedures to deal with GBV. As women might be living with their abusers in GBV situations, reporting through standard helplines might not be possible. New reporting avenues such as texts and other no-call methods can help. For instance, in Canary Islands in Spain, women can use the code “Mask-19” to alert pharmacies about domestic violence, which will bring in police support.

The increased incidence of intimate partner violence in several countries, including Malaysia, prompted many international organisations to call on governments to consider the gendered impact of the pandemic. Acknowledging the “horrifying global surge in domestic violence,” the World Health Organisation (WHO) specifically urged all Member States to adequately respond to violence against women and to include women in preparedness and response plans for COVID-19. The WHO also makes specific reference to the importance of resourcing the response, and identifying strategies to make services accessible amid the enforcement of physical distancing measures.

UNDP has been proactive in dealing with increased GBV across the globe. It published a briefing note with a set of strategies and recommendations that UNDP and other UN organizations can take to prevent GBV and support survivors. It has also published recommendations on what national response to GBV in COVID-19 should include, presented in the infographic below.

Source: UNDP brief on Gender-based violence and COVID-19

As Malaysia slowly emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic and the new normal sets in, it is crucial that the government, through the leadership of the newly formed national committee on handling domestic violence, take heed of these recommendations.

While this pandemic has revealed the vulnerabilities of our social, economic, and political systems, it has also given us an opportunity to dive deeper and confront underlying issues that have, for so long, hindered survivors’ access to justice.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jun Jabar, programme analyst, and Tan Siew Mann, project manager, for inputs and comments.

About this blog's co-author

About this blog's conversation partner

Since 1982, Women’s Aid Organisation has provided free shelter, counselling, and crisis support to women and children who experience abuse. We help women and their children rebuild their lives, after surviving domestic violence, rape, trafficking, and other atrocities. Learning from women’s experiences, we advocate to improve public policies and shift public mindsets. Together, we change lives.

This blog contains information and perspectives of the individual authors and does not indicate any formal endorsement by UNDP Malaysia or the conversation partner’s organisation, nor does it indicate provision of any technical support in their implementation. UNDP Malaysia is not responsible for content provided in any of the external sites linked to this article. This is purely for informational purposes only.

Locations

Locations