Blog authored by: Henghwee Koh, Advisor, Behavioural Insights Team Singapore. Karen Tindall, Principal Advisor, Behavioural Insights Team Australia. Ayesha Junaina Faisal, Programme Officer – Governance, UNDP Maldives.

On the International Day of Women and Girls in Science it is worth remembering that ‘seeing is believing’ - a principle Iris Bohnet highlights in her book What Works: Gender Equality by Design.[1] When we have a preconceived idea that a career is dominated by men, seeing a real-world example of a woman in the role can break that stereotype and challenge our assumptions about what is possible. We used this principle in a recent piece of work in which we designed an intervention for one of the most geographically dispersed countries in the world, the Maldives. We connected young women with relatable role models in Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths (STEM) and inspired them to consider STEM as an ambition that they could rightfully aspire to.

Opportunities and salaries in STEM have been growing across the globe, but women have not benefited equally from this growth.[2] This is particularly true for women in the Maldives, who are less likely than men to work at all.[3] This is partly driven by strong cultural expectations for women to take care of their family first, meaning that young girls and women rarely have STEM role models to follow. This creates a vicious cycle. Women don’t see women in those roles, so they don’t relate themselves to those roles and don’t apply for the roles. Not applying for those roles means that there are fewer women to be seen in those roles.

Ambitions for careers in STEM jobs are often curtailed early. Many girls in the Maldives already take STEM subjects at O’ Levels (when they are approximately 16 years old), but drop them afterwards. Therefore, during the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, both globally and in the Maldives as well, we worked with National Institute of Education and Women in Tech Maldives to encourage girls to stay in education and continue with STEM subjects during A’ Levels and beyond.

Co-designing the intervention

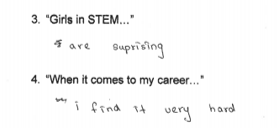

We spoke to 73 female students aged 13yrs to 23yrs on the islands of Malé and Kulhudhuffushi about their ambitions. The two key barriers preventing girls from aspiring to STEM careers were 1) their stereotype of what a STEM career looks like and 2) their mental model of the sort of person that works in STEM. Girls drew inspiration for their careers from a very small circle -- mostly from their schools and families. They often saw female relatives staying home to take care of children or becoming teachers, while only male relatives became engineers or computer scientists.

On the flip side, additional exposure was a significant influence in cultivating girls’ interests and dreams. During our fieldwork, we found a cluster of girls who all wanted to be psychologists because a psychologist had recently given a talk in their school. There was also a cluster of girls in another school who were enthusiastic about criminology because their favourite show was ‘Brooklyn 99’.

Taking inspiration from this and the academic literature, we designed and piloted an intervention to show students’ female role models in STEM: we invited Maldivian women in STEM (working in the area of Data Science and Software Development) to give a talk to girls in the 10th grade who were about to take their O’ Levels. They spoke about their own journey to pursue a STEM career in Maldives, their struggles and motivations, and reflected back on what they were like when they were 16 years old.

From the academic literature, we know that women are likely to be less interested in pursuing careers if the fields seem to be heavily male dominated, while having a female role model increases performance and interest in STEM subjects.[4] We hoped that connecting girls with a female role model in STEM would inspire more girls to pursue STEM careers.

Piloting and iterating with students

We piloted and iterated the intervention in four schools across the Maldives (in Haa Dhaalu Atoll, Gaafu Dhaalu Atoll and Gaafu Alif Atoll) and gathered feedback from eighty 10th grade girls. We tried out different session formats - in one version the speaker pre-recorded an interview and then video-called in for a Q&A session with the class; in another version, the speaker gave the whole presentation as a ‘live’ video-call in which none of the session was pre-recorded; and in another version the speaker shared her screen to demonstrate a fun interactive coding exercise, as well as doing the whole session “live”. After each session, we asked the girls about the experience of seeing this speaker.

It was important for speakers to talk about their struggles, as well as their achievements. Stories about struggles helped students feel speakers were more relatable and that STEM careers were more achievable. For example, after one speaker shared that she had actually not done well at O’ Levels, several girls said that they felt encouraged that they did not need perfect academic performance to pursue a fulfilling career in STEM.

We found that the ‘live’ presentation with the demonstration of a coding exercise was the most popular approach. The live presentation gave time for the speaker to build rapport with the class and the coding demonstration made the concept of a STEM career seem more real and practical.

The sessions did indeed broaden girls’ horizons -- when asked “What part of this talk surprised you the most?”, a substantial number of girls responded with a variant of “there are a lot of opportunities for women in STEM fields”, ranging from being surprised that women could be successful in STEM fields, to being surprised that women could have careers in STEM at all.

The challenge of how we connect young people to local and global opportunities was complex even before COVID-19 forced many into virtual classrooms and work-from-home offices. And as long as a stable internet connection is available, then this is a low-cost, time-efficient, and effective way for girls to see a relatable and successful STEM professional and to believe that it is a viable career pathway. On the back of this successful pilot, UNDP Maldives along with the National Institute for Education, Ministry of Communication, Science and Technology and Women in Tech Maldives with the support from the Government of Australia are working together to scale this intervention nation-wide to reach more girls and women in actualizing their aspirations for a career in STEM.

---------------------

[1] Bohnet, I. (2016). What works: Gender Equality by Design’. Harvard University Press.See also: Dasgupta, N., & Asgari, S. (2004). Seeing is believing: Exposure to counterstereotypic women leaders and its effect on the malleability of automatic gender stereotyping. Journal of experimental social psychology, 40(5), 642-658.

[2] UNESCO Institute for Statistic. (2015). Women in science: quarterly thematic publication. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000235155

[3] United Nations Development Program. (2019). Human Development Report 2019: Inequalities in Human Development in the 21st Century. Retrieved from http://hdr.undp.org/sites/all/themes/hdr_theme/country-notes/MDV.pdf

[4] Smith, J. L., Lewis, K. L., Hawthorne, L., & Hodges, S. D. (2013). When trying hard isn’t natural: Women’s belonging with and motivation for male-dominated STEM fields as a function of effort expenditure concerns. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(2), 131-143.

For more information contact: karen.tindall@bi.team

Locations

Locations