By: Aseel Bokai , Design-Thinking Specialist, UNDP Accelerator Labs, Jordan

Our Portfolio Journey: A Bricolage of Voices, Ideas and Learnings

November 30, 2022

“Today, you don’t need to design a different bus to design an entirely new bus system, moreover, you don’t need to remake a government to deliver the structures people need to improve their lives” - Kuang et al, 2019, User Friendly, p.286

As our realities continue to change and evolve, the challenges we address become more complex yet demanding simpler solutions. And to co-design and identify opportunities that respond to evolving circumstances, we must approach the portfolio as a journey that stimulates experiences for different stakeholders, where each step in the process is identified as an opportunity to invite multiple perspectives and generate new learnings.

What follows is a run-through of insights and reflections from our non-linear portfolio journey concerning our work in rural areas in Jordan:

Scaling Deep: Inwards vs. Outwards

One of our core beliefs in the Lab is that individuals living in an experience are best suited to solve it. With this in mind, we conducted field visits, observations, and virtual interviews with individuals living in rural areas to explore our hypothesis that we’ve developed during our foresight session. By speaking to housewives, teachers, store owners, farmers, butchers, civil defense workers, etc., we were able to gather data about the perceptions of a range of individuals about opportunities outside and inside of their immediate areas, understand ways they find jobs, market their products, and solve their problems.

Being left with diverse information and insight into people’s fears, hopes, and ideas felt like an opportunity yet somewhat a responsibility. I had many thoughts and questions running through my head which left me wondering:

- How do we ensure that we understand our problem space correctly?

- How do we ensure that the side effects of solutions that we test and scale do not impose future problems?

With this in mind, I started building a research wall to surround the team with our ongoing research from four locations in Jordan, including Northern Shouneh, North Eastern Badia, Madaba, and Theban. The intent was to develop our understanding of the challenge by making sense of the patterns in our collated data, whilst keeping an eye for what’s already strong in the context and reflecting on what individuals are longing for.

Data wall with quotes, images, maps, observations and assets.

Our clustering exercise surfaced different groupings for the team to consider. Categories ranged from

values “ I feel proud of my daughter who studied at university. “, to frustrations “Transportation here is expensive and inconsistent! ”, to adaptations ranging from “I use Whatsapp to receive orders on pastries.” to “ I’m experimenting with feed by using leftover food for fish”.

Resisting the urge to experiment with ideas that emerged from individuals we spoke with, we had to take a step back to avoid our group’s confirmation bias. Considering this, I asked myself:

- What points of view are we missing from the team?

- Who can we learn from in the UNDP that is closest to the context of our challenge?

Digitizing the data wall for virtual collaboration.

Accordingly, I digitized the research wall onto Mural to conduct three virtual collaborative sessions with a mix of junior and senior staff members from UNDP pillars. The internal sense-making exercise aimed to invite pillar teams to review our research and to cross-check our data points with their expertise.

Participants voting on three key insights from the research that are new to them.

Zooming in

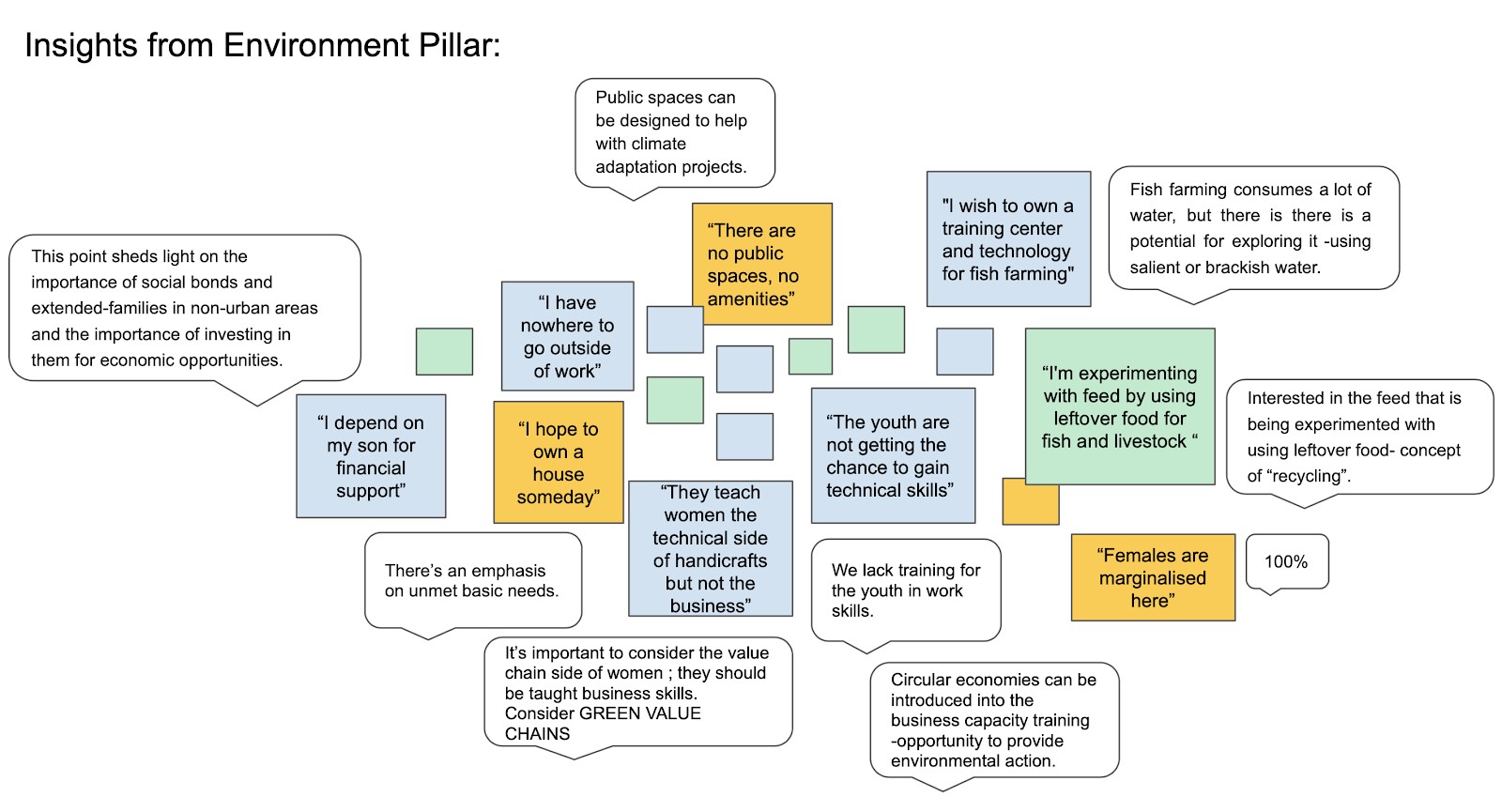

Tapping into the knowledge of the pillars provided us with valuable feedback and conflicting perspectives on recurring themes in our aggregated field research. At first glance, it was noticeable that there were many unmet basic needs in rural areas and that COVID-19 has heavily impacted people’s livelihoods, including the mental and economic well-being of individuals.

Although Jordan’s handicrafts sector plays an effective role in economic development, some projects as voiced by pillar members are ‘hit and run’ interventions. It was evident from our research that there’s a lack of business capacity training for women and little proficiency in English may restrict the recognition and advancement of practitioners.

A critical discussion around natural resources was raised. Some pillar members observed that new generations have abandoned existing resources and projects that don’t utilise existing assets create deviations. While some sensed from the insights that women are aspiring to their traditional roles in society, and many individuals are seeking inherited jobs instead of new opportunities.

Altogether, a feeling of lack of hope, frustration and mistrust was apparent, but what seemed promising is that individuals are attempting to cope with their realities in different ways and are searching for solutions to their problems.

The adoption of technology to acquire new skills and reach customers, the presence of social bonds and extended families, and the experimental mindset of individuals were identified as assets and change enablers.

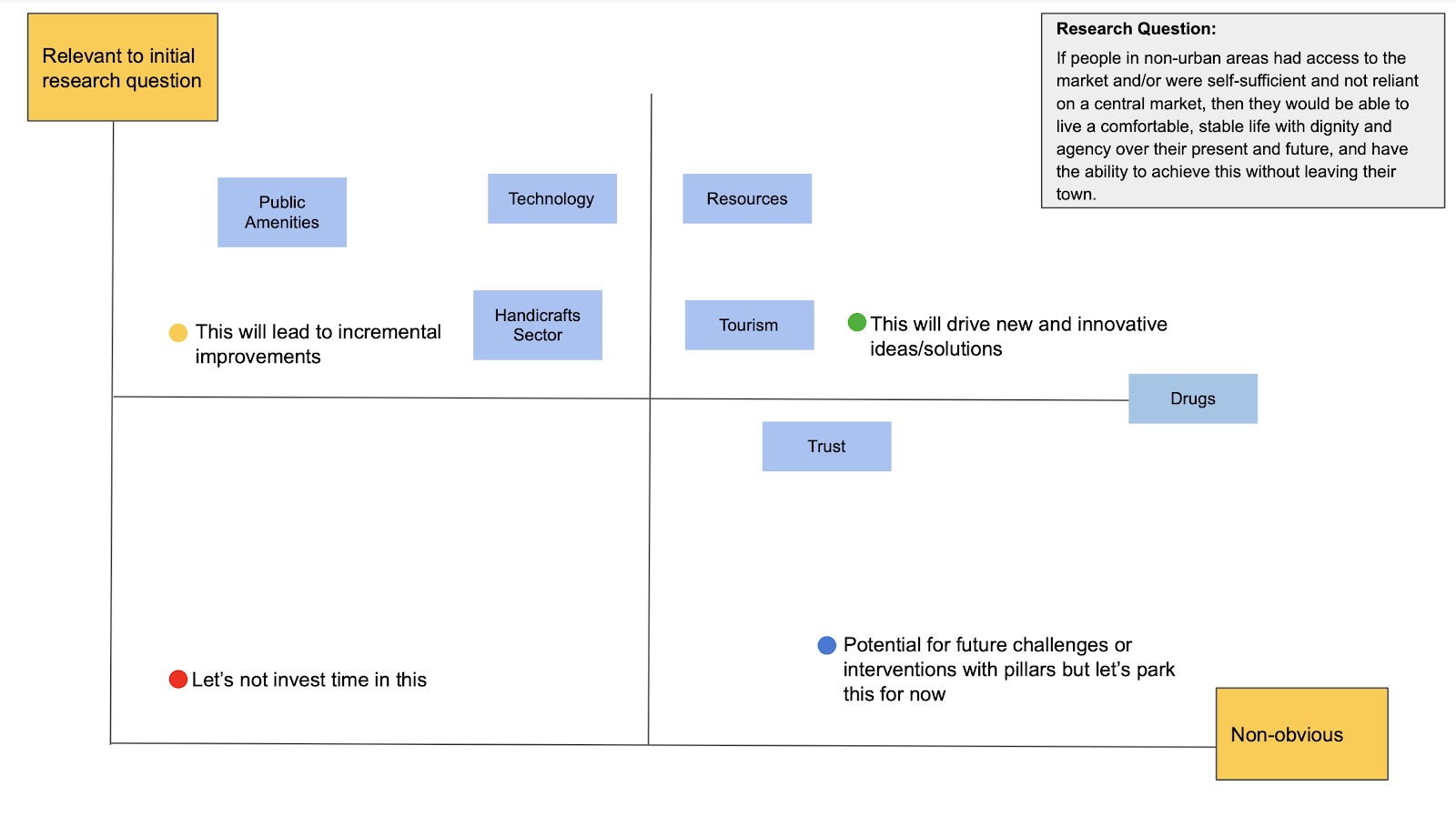

We concluded the sessions by discussing emerging themes and overlaps between our research and the pillars’ existing projects for potential interventions. Following our synthesis, we, as a Lab, identified key areas related to our challenge, including:

- Technology

- Public Amenities

- Trust

- Handicrafts Industry

- Resources

- Tourism

- Drugs

To revisit our hypothesis, we mapped the key themes in a 2x2 matrix with two variables in mind: 1) Relevance to the research question. 2) Novelty to the challenge. ( Refer to the image)

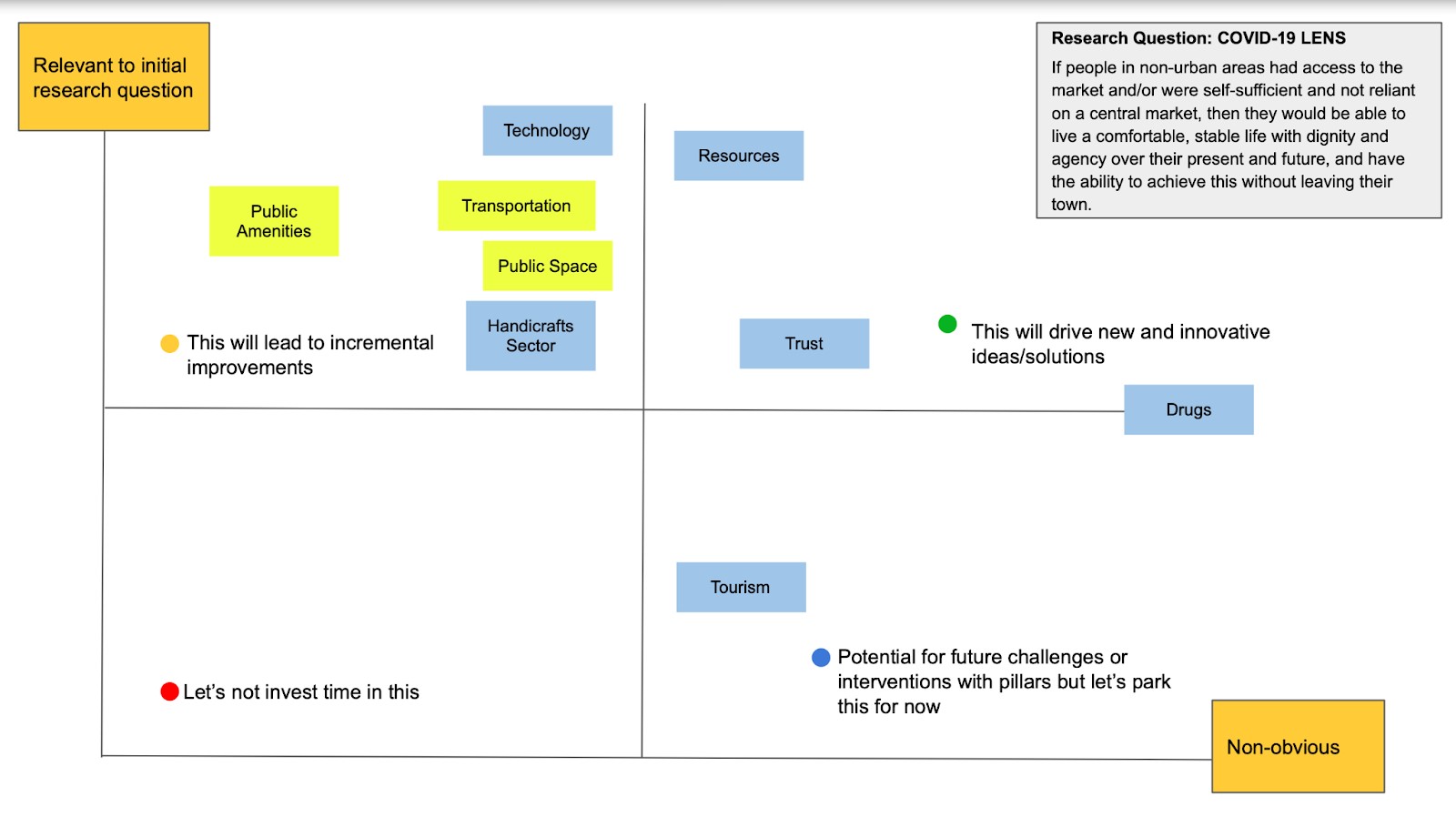

We then did an iteration of the exercise to examine how the priority order of areas may change through a COVID-19 lens.

( Refer to the image

Initially, we assumed that access to the central market was a direct factor contributing towards the comfort, stability and sense of agency of individuals in Jordanian rural areas. Scaling deep internally and externally has revealed to us the network of interconnected issues, factors and players that shape the present and future reality of individuals. We’re still looking forward to seeing where this portfolio journey will take us, as we further embrace its complexity by digging deeper to locate overlaps where solutions could emerge.

At last, the main takeaway for me from our ongoing process is that the success of any portfolio is not only measured by the solutions and interventions it creates, but also the spirit that guides it!

Locations

Locations