Adopting Portfolio Approaches in Kazakhstan’s Economic Capital

Almaty Air Quality Portfolio

July 12, 2024

In tackling escalating social and environmental challenges, it is becoming clear that traditional project-based innovation methods, with their predefined objectives, outcomes and fixed timelines, often miss the systemic complexities of urban transformation. This includes tackling challenges like transport optimisation, energy transition, and air pollution. In the past few years, an increasing number of development actors, including UNDP, have acknowledged these shortcomings and pivoted towards more nuanced and responsive strategies. A shift to the 'portfolio approach' represents this change in perspective, offering a framework that is flexible, integrative, and adaptable. In this blog, we present a case study that adopts this approach to combat persistent air pollution in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Reflecting on our collaboration with Dark Matter Labs—a strategic design and research lab—we share our insights and experiences from this methodology in practice. Our intent is to contribute to a growing dialogue on innovative methods, focusing on both the process—the ‘how’—and the objectives—the ‘what.’

Portfolios as a Method

As the first initiative in Kazakhstan to adopt a ‘portfolio’ approach, ‘Breathing City: Clean Air in Almaty Through Joint Efforts’, specifically engaged with the concept of portfolios as a dynamic model for organising around specific missions, such as clean air and improved public health. Originating from the field of finance (as primarily a risk management tool) and later adopted in the field of policy innovation, portfolios are understood as a network of actions, actors, resources (assets) that drive resilient transition processes. Unlike the conventional method of allocating funds and resources to sector-specific, single-point solutions that address a relatively narrow set of issues, the portfolio framework allows for the aggregation of diverse initiatives within a coherent strategic vision, enabling them to mutually reinforce each other. Moreover, this intention to consider synergies between different initiatives translates into a method of design, delivery, and management that is much more distributed and collaborative, rather than centralised.

However, the portfolio approach is not without its challenges. Institutionalising this method demands substantial efforts to transform procurement, monitoring and evaluation (M&E), and various legal instruments that have traditionally governed the life cycles of large development programmes. The novel approach of clustering initiatives by missions and synergies rather than by traditional sectors may complicate efforts to attract financing and government support, particularly when it diverges from established investment and planning cycles. Building new capabilities and institutional knowledge to enable the shift towards the portfolio approach also remains a continuous challenge. Recognising these obstacles, our project sought to refine and adapt the portfolio model to the unique context of Almaty’s air quality challenge.

Hypotheses for Change

Our initiative was built on several key hypotheses aimed at enhancing efforts in air quality action in the city, an active domain spearheaded by committed local actors engaged in advocacy, research, and technological innovation.

Reframing the issue of air pollution to emphasise its health and economic implications would mobilise a broader range of stakeholders

Bringing in new actors could help shift the conversation and action on air quality, and thus enhance existing efforts by diversifying strategies and perspectives

By embedding the portfolio content in municipal and local partner plans and aligning with a new project office in the local government (Almaty Akimat, and its subsidiary bodies like Almaty Development Centre), we could develop a strong pathway for implementation

Translating Portfolio Method into Project Processes

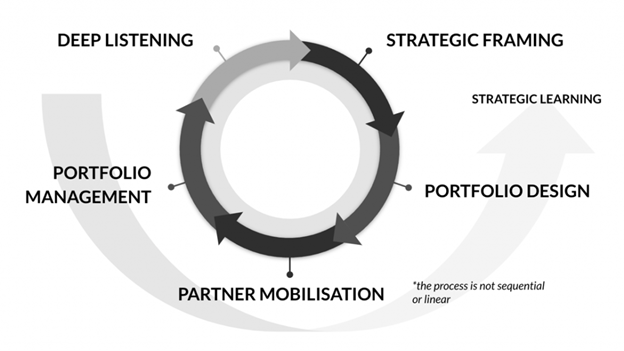

The portfolio method, far from being a fixed framework, is inherently evolving and adaptive, reflecting the contributions from diverse participants and the specificities of the local context it is being initiated in. In the case of the Almaty air quality portfolio, we adapted it as a step-by-step process that integrates research, co-design processes with local stakeholders, and a cycle of review, learning and further development.

Deep Listening: Enabled by stakeholder interviews and research — focusing on underlying barriers and innovations

Strategic Framing: Focusing on strategic alignment with existing initiatives and identifying suitable scale and scope

Portfolio Design: Enabling multi-stakeholder workshops for ideation and building legitimacy and alignment

Partner Mobilisation: Moving towards shared accountability, multi-partner collaboration and new forms of governance

Portfolio Management: Building tools and metrics for continuous portfolio development, implementation and strategic learning

Working with a map of challenges

Deep Listening and Strategic Framing

Our initial step centred around deep listening, a phase marked by stakeholder interviews and desk research. This allowed us to uncover the nuanced challenges and opportunities within the Almaty context, focusing on the underlying barriers to clean air and the potential levers for change. In April 2023, we held an in-person ‘sensemaking workshop’ inviting a diverse range of stakeholders — from local experts to community organisers — to share, validate and strengthen the insights gathered from the research. (More details about the process in our first blog.) Some practical tools that we adopted in an in-person and hybrid workshop context were the Five Whys framework, which allows collaborative investigation into root causes of problems, and the challenges and initiatives mapping canvases (see image below), which provide a framework that incorporates insights from desk research and invites participants to proactively add missing elements.

As a crucial step in the portfolio process, strategic reframing utilises insights from the identification of structural challenges to pinpoint gaps and highlight potential levers of change. Through participatory sessions, reframing becomes an opportunity to introduce diverse viewpoints into the portfolio, creating richer and more differentiated narratives as well as new entry points for action. In the case of Almaty, strategic reframing involved looking into one of the root causes of the challenge identified by local stakeholders: the fact that air pollution as an issue is often overshadowed by concerns for economic development because it is largely framed as an environmental issue. Through reframing, we were able to construct a narrative around air pollution that highlighted the economic implications and adverse health effects, particularly on children, which opened new avenues for collaboration between schools, parents, businesses, and medical researchers. This not only broadened the scope for advocacy but also facilitated knowledge sharing and potential for collaborative action.

Often, introducing a systemic perspective into an existing issue necessitates an expansion of the problem space, because root causes of a problem tend to overlap, and this exploration of common ground allows us to see how seemingly discrete sectors or domains of problems are in fact interrelated and interdependent.

Portfolio Design and Partner Mobilisation

The next phase of the work involved a series of collaborative ‘design sessions’ to explore new actions and initiatives that could be integrated into the portfolio. The process not only helped generate innovative ideas but also built legitimacy and alignment among stakeholders, ensuring broad-based support for the portfolio’s objectives.

Instead of being a separate phase, partner mobilisation is usually embedded in the ongoing participatory activities that we hold throughout the portfolio design phase. This is to ensure a smooth transition to the implementation phase, and to avoid treating implementation as a mere exercise of delegation and delivery. In the Almaty portfolio, we introduced an additional step of creating a ‘nested’ portfolio—the ‘Safe and Green Streets’ initiative, which strategically connected several initiatives (or “options”) within the larger portfolio to align with critical developments in the city (specifically the new General Plan of Almaty by the government, and mandates of key stakeholders). This was an effort to improve the chances of investment, in a context where portfolio-based investments were rare, and to secure the buy-in of key local stakeholders who may not be familiar with the portfolio framework.

As such, portfolios emerged as a tool to move beyond traditional ‘master plans’ and municipal planning, which often result in extensive lists of actions that few people engage with and that become fragmented during implementation, typically being delegated to the most economic bidder. While the participatory portfolio design sessions helped counter the centralised and top-down nature of planning, transforming it into a more distributed and iterative process, an additional step is needed to make it truly actionable. Through our experience in Almaty, we recognised that to advance a portfolio of actions beyond a static list, it must be integrated into ‘pathways’ aligned with funding opportunities and potential coalitions of actors.

Portfolio Management and Strategic Learning

Portfolio management involves a dynamic process of strategic review and learning, combined with institutionalisation and mainstreaming, which is what we had attempted to do through developing a ‘nested’portfolio, aligned with municipal strategies. It recognises that portfolios need to be continually updated and respond to the latest information, learning through emerging partnerships that form along the way. In the Almaty portfolio process, we began with an open inquiry (not just a hypothesis that was going to be tested and evidenced), which was further defined through stakeholder interviews, challenged and validated continuously throughout the collaborative portfolio design process, and re-worked again through the formation of new partnerships. The evaluation of a portfolio does not happen at the very end—instead, it is iterated at multiple points throughout the process, which allows room for emergence and an ability to respond to the changing conditions of the system.

Lessons Learned and Looking Ahead

As a methodology, the portfolio approach is continuously evolving. Typically, the concrete outputs of a portfolio design process include a list of actions—also referred to as options, interventions, or experiments—that are strategically implemented by various actors. These actions are often clustered together to highlight adjacencies, connections, and potential synergies. In the Almaty portfolio, actions were organized under three strategic outcomes: 1) Improving health with a focus on families and children; 2) Building a Green Economy; and 3) Fostering Green Urban Development. These clusters align with the strategic framing of the portfolio, which addresses air pollution as both a health and economic issue. As detailed earlier, some initiatives in the portfolio were strategically grouped under the ‘nested’ portfolio of ‘Safe and Green Streets.’ This initiative envisions a network of interconnected innovations centred around schools, involving retrofitting for energy efficiency, low-emission zoning, urban green infrastructure improvements, and tactical urbanism for community engagement.

As we continue the first stages of implementation, which includes among others a small-scale experiment centred on tactical urbanism, one critical reflection has emerged: a mere list of actions—or a portfolio of actions/initiatives—is insufficient. Greater effort is required to understand and articulate how these diverse actions can be implemented in real-world contexts. In essence, a more nuanced ‘portfolio’ approach to ‘implementation’ is necessary to ensure these strategies are effectively realised.

As a first step, we are exploring how we can expand and complement the portfolio of actions with additional data and insights such as a list of relevant actors and assets in the ecosystem. The identification of relevant actors within the system highlights the potential for new, sometimes unexpected alliances that span institutions, spaces, and narratives. Similarly, identifying the assets available within the system—from financial resources and regulatory frameworks to democratic legitimacy—underscores the critical role of resources and constraints in shaping action. These assets do not merely facilitate action; they define the boundaries of possibility, encouraging, constraining, and aligning actions within the urban ecosystem. Ultimately, a portfolio that effectively conveys how multiple connected actions, delivered through a coalition of diverse actors who share resources and build on each other’s capabilities, can significantly amplify impact.

Our initiative on improving air quality in Almaty has been a journey of discovery and learning. As the portfolio advances into new phases of implementation, it is progressively handed over to local actors who institutionalise and tailor the process to their context. Concurrently, we continue to explore ways to scale up the venture and apply the lessons learned to initiate or expand larger UNDP programmes both within Kazakhstan and beyond.

Locations

Locations